Callum Macgregor

Research Ecologist, British Trust for Ornithology

In late January 2021, the ECHOES project team fitted GPS-tracking collars to three Greenland White-fronted Geese (GWfG).

Each winter, very small numbers of this rare and declining subspecies choose to see out the coldest months in Wales (with larger numbers in Ireland also a focus of ECHOES project). The best-known flock, on the Dyfi Estuary, is now around 12 birds: while a second group (flock size unknown) was occasionally reported on Anglesey/Ynys Môn.

This species is notoriously secretive and highly sensitive to disturbance from humans, so to learn more about their behaviour, we turned to satellite tagging. Fitting a harmless lightweight collar around the neck of a goose, incredibly, allows us to determine their location on the Earth every 15 minutes down to roughly the nearest 20m (similar technology is also being used to track Curlews in the ECHOES project, with their tags mounted on the birds’ backs).

Intensive searching found a flock of 18 birds on Anglesey in December 2020, and the field team, led by Senior Research Ecologist Dr Rachel Taylor, were able to capture eight of the birds and fit satellite-tracking tags to three of them during January.

It’s early days within the GWfG element of the ECHOES project. Two months’ worth of data were collected before the geese departed for their summer breeding grounds in Greenland and is now in the process of being analysed. We all have our fingers crossed that when the flock returns later this autumn, our tagged birds will still be among them. If they are, we will be able to download and analyse a huge additional batch of data showing their journey from Anglesey to Greenland and back, as well as vital information about how they spend the critical first days after arriving back from migration on Anglesey. We also plan to complement this with data from birds overwintering in Ireland, to see whether the same factors affect flocks living on both sides of the Irish Sea.

Nevertheless, these three remarkable birds are already providing new insight into how Anglesey might look through a goose’s eyes. All three birds spent the vast majority of time in close proximity to each other, but very occasionally separated. This corresponds with what we already knew about the flock, which largely sticks together but occasionally splits into at least two distinct family groups. Our data, therefore, suggests that we have tagged birds in both groups (with luck, we might be able to confirm this once the birds return from migration).

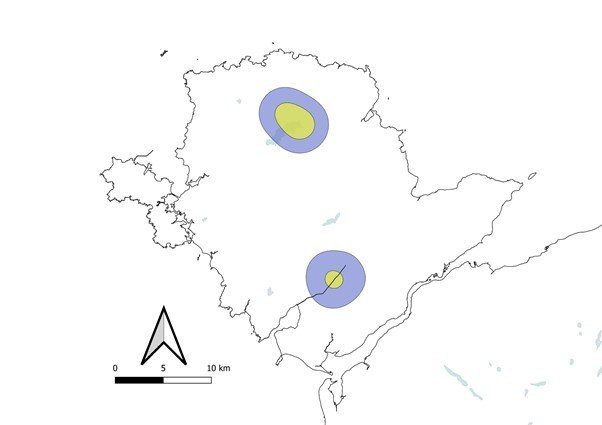

The group split most of their time between two areas in central Anglesey, one of which centred on the RSPB’s Cors Ddyga reserve. As February changed into March, they became more sedentary and focussed their time on a smaller area at just one of those sites. We know that these birds are sometimes observed at other sites on Anglesey, but they were completely faithful to just these two sites during the two months after they were tagged this spring. It’s possible that they move to different sites at different times during the winter in order to capitalise on the best feeding grounds, so this is another question that might be resolved once the birds return this winter and provide us with some more data!

Matching up GPS fixes to habitat data reveals a clear day-night pattern in where the geese choose to spend their time. Almost the entire daytime is spent in pastures – prime grazing land where the geese can feed to their heart’s content. After dark, the geese returned every night to one of two large waterbodies, roosting on deep water (presumably to reduce their risk of predation). Further analysis will help us to understand these choices at much finer resolution – which fields do the geese prefer to feed in, and what are the characteristics of these fields? Why do they always roost on these two waterbodies, rather than any of the many other still waters in the area? Beyond this, we hope to understand what factors influence the birds’ choice to spend time at each site, and particularly what factors cause them to invest precious energy into switching from one site to the other – which they did on a near-daily basis during one critical week in late February.

Among the possibilities, we’ll investigate variables relating to climatic conditions – a key focus for the ECHOES project, which seeks to understand how ongoing climate change will impact GWfG and Curlews around the Irish Sea. The bizarre circumstances of conducting this work during the pandemic has also offered us a completely unique opportunity to link changes in goose behaviour to key dates – such as March 13th, when restrictions in Wales changed from “stay at home” to “stay local”. These geese are generally thought to avoid humans as much as they can, so did the increase in recreational activity around this date – especially at RSPB Cors Ddyga – influence their behaviour? Watch this space, for answers to this and more!

The map below shows how our flock of GWfG split their time between two locations in Anglesey. The three birds spent approximately 95% of their time within the areas enclosed by the two blue circles, and 50% of their time within the smaller yellow circles.