By Holly Sayer, Field Botanical Surveyor.

As a botanist, most of my work is centred around the spring and summer months, so to be involved in a project where surveying is focused over the winter period is a novelty. It does however, come with its own set of challenges. In a temperate environment such as the UK, plants and grasses are mostly dormant during the winter season. This makes identification more testing as most of the foliage and flowering parts are either less visible or non-existent. Add to that the sideways rain and 20 metre visibility that is common on the coastal marshes of West Wales in winter, and you have what we like to refer to as external variables.

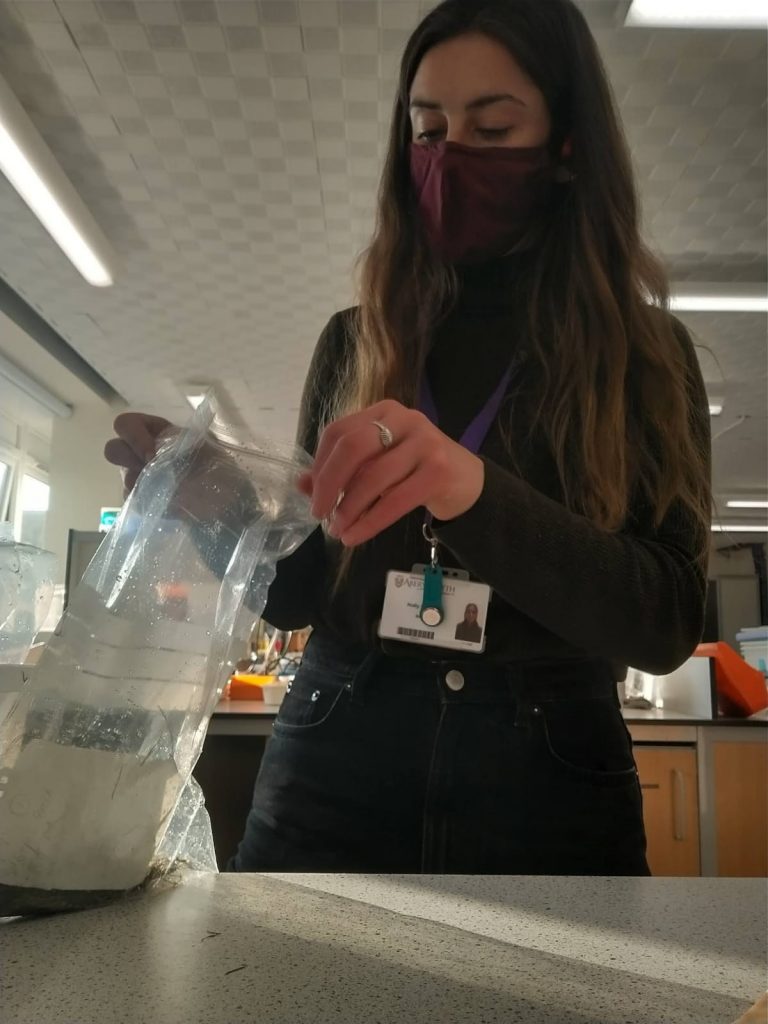

The ECHOES project fieldwork that I am conducting is focused on the wet grassland and saltmarshes around Ynys Hir on the Dyfi estuary. The project is designed to assess whether rising sea levels could impact the winter feeding grounds of the protected population of Greenland White-fronted Geese. To do this, I head out on to the marshes to collect samples of their food plants. These samples are taken back to the lab at Aberystwyth University, where I dry and sort the material before sending them off for nutritional analysis at the biochemical lab.

It’s this short period between November and March, when the geese are present on the marshes, that defines my winter survey schedule. I choose the best days of the week and armed with my GPS, sample bags and a flask of hot coffee, begin the walk from the Ynys Hir car park to the sample points. Once you cross over the Borth to Aberystwyth trainline you’re in the saltmarshes, which is not accessible to the public, so the only footprints I see here are my own and the geese.

It is this seclusion from other humans due to the twice daily tides that give the saltmarshes their ethereal and remote beauty. As you navigate across the vast network of the estuary channels carved by the receding tides, your focus is on remaining upright in the silty estuarine muds. The silence is punctuated occasionally by the atmospheric calls you only get from wetland bird, such as the Curlew, the Redshank, the geese, and the unlikely trundle of the Aberystwyth to Borth train in the distance.

The fieldwork was designed around the known food plants of the GWfG, to try and understand why the GWfG choose a particular area, even though the same food plants are available in other areas of the marsh. We collect the known food plants of the GWfG from a cross-section of habitats within the marshes to identify if there is a difference in the nutritional value within a given habitat type or area of the saltmarsh. Could the geese be repeatedly choosing these fields because the plants in them are more nutritionally dense, or are there other factors at work?

Sea level rise makes these coastal areas particularly vulnerable to habitat loss. If the GWfG are choosing these exact fields for a particular reason, could the viability of the population be at risk if certain areas of the marsh are lost?

These over-wintering grounds are a vital habitat for the geese to nourish themselves and get themselves in good shape to make the arduous journey back to their summer breeding grounds in western Greenland. By understanding the nutritional value of the food sources and food plants across the marsh, the ECHOES project hopes that this information can assist land managers to adapt to sea level rise and ensure that suitable habitat is available.

Heading back to the car after a long day of sampling with the ever-changing character and mood of the day reflected off mudflats, I am reminded how important these unique habitats are.